I recently had a conversation with a friend in which he suggested that Ivermectin had been shown to be an effective treatment for COVID-19. My first instinct was to think that I would probably have heard more about this drug via my research networks if it had been shown to be effective, but since I didn’t know any specifics on the matter I decided to just take the information on board and look it up later. Just a few minutes ago I started that search, but stopped when it struck me that the processes I use to search the internet are probably very different to those that my friends and family use. This comes from a place of privilige – the privilige to have been born in a country and circumstances where I could study science at university and then spend many years completing a research PhD, all funded by the Australian tax payer. In turn, I feel that researchers like myself have a responsibility to share the knowledge we acquire with the general public – hence why I am a staunch advocate for open science. But as much as I am hoping to help address misinformation on a global scale, I feel I could still be doing more on a local scale to help friends and family navigate the tide of misinformation that is all too readily available these days. As such, I felt that there might be some small value in paying close attention to the steps and reasoning that I take when hunting for reliable information on the internet, so that I can relay those steps to other people. And since I was at my computer anyway, I figured I may as well record those steps here, for anyone who may be interested. This blog post represents the steps that I took to investigate Ivermectin, written in real-time as I undertake each step.

-

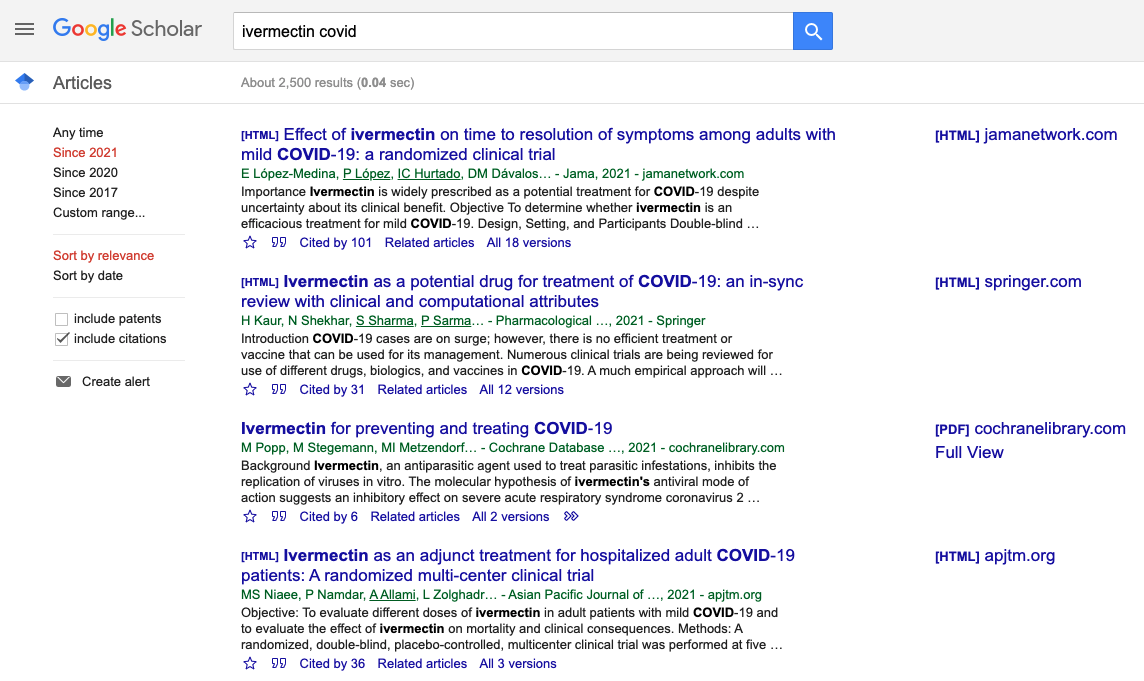

Go to Google Scholar. First and foremost, the regular Google website uses an algorithm designed to maximise Google’s advertising revenue, rather than deliver reliable information. So going to Google for reliable information is like asking a used car salesman to show you how to make lemonade – you might walk away with a lemon but it’s not the result you were looking for. In contrast, Google Scholar only indexes scholarly articles – actual research conducted by researchers. The algorithm is still controlled by Google and I’d much prefer that it were open source and researcher-controlled, but that’s a fight for another day. For now, we know that Google Scholar returns comparable or possibly even better results than its competitors (Scopus/Web of Science, also privately-owned) and so is, as far as I know, the best public-facing option for finding reliable information.

-

Enter “ivermectin covid” into the search bar. This brings up a number of results. Ordinarily, I would just start from the top here and work my way down, looking at the title and date of each article, but given how rapidly COVID research is evolving, I wanted to make sure I had the latest information, hence…

-

Click ‘Since 2021’ (left hand of window). This now brings up a list of more recent articles, like so:

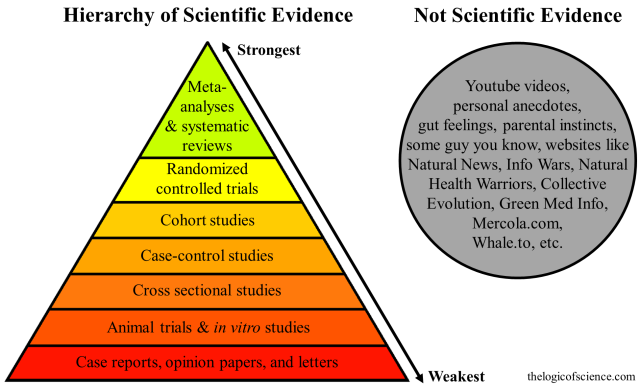

- Work down the list. What am I looking at? Well, this isn’t my field of expertise, so I’m not expecting to recognise any names. Instead, I’m looking at the article title and the source, i.e. the journal and/or publisher. The first article sounds like a report on a single study. After doing many years of science, I no longer trust single studies to tell me anything reliable – it’s all too easy to find a significant result and get it published, even when there’s no real effect to be found. This is because the statistical tests we apply use arbitrary cut-offs to determine the ‘significance’ of the result. In a study that uses a 5% cutoff (p<0.05), 1 in 20 studies will find a significant result just by chance alone. On top of this, journals are much more likely to publish significant results than they are null results, which can pressure researchers into using less-than-ideal research practices. Together, these factors mean that over half of all published research findings are false and that it’s a mistake to trust the findings of any single study (I learned this the hard way, getting fixated on a single study in my PhD and then wasting months trying to replicate the effect). So, rather than trusting the findings of single studies, I now only really start to trust findings once I’ve seen the same effect in at least a few studies – and even then, I remain skeptical. What I’m really looking for is a meta-analysis or a systematic review. These are both special types of articles that don’t actually conduct original research themself, but rather condense all of the known information on a topic into a single paper. Because they draw on information from multiple sources at once, they are much less prone to chance effects, and many will also attempt to account for publication bias in the literature. The following slide captures this, showing the relative strength of evidence as you move down the hierarchy from meta-analyses/systematic reviews to single randomized controlled trials and then further down to even less reliable sources of information.

-

Almost click on the second article. This one looked promising, as the title indicated it was a review (rather than a single study) and was directly related to my search. But I didn’t recognise the journal name and was also was thrown off by the word ‘in-sync’, so I took a mental note to look at this study if there wasn’t anything more reliable to look into.

-

Click on the third article (Ivermectin for preventing and treating COVID‐19). Bingo. The title is clear and simple, suggesting it’s about what I’m interested in and nothing else. But above all, I recognised the word Cochrane, which I know to be associated with the reliability movement in Medicine. As far as I know, Cochrane reviews are the highest-quality reviews of medical literature, using rigorous and systematic approaches to select the highest-quality evidence (e.g., randomised controlled trials) and analysing it in ways that control for bias as much as possible. As far as medical evidence goes, Cochrane reviews are the cream of the crop.

-

Read the abstract. Background, objectives, methods, selection criteria, and data analysis/collection all seem ok to me, at least as much as I understand this area (which is only in broad terms, common across all research domains). Only “14 studies” were analysed, which isn’t a huge number but should be enough to make some decent inferences. The abstract then lists multiple results, all of which begin with “We are uncertain whether…” or “Ivermectin may have little or no effect…” and end with “very low-certainty evidence” after the statistical results (the part within the parentheses).

-

Read the conclusion. This part is pretty self-explanatory: “Based on the current very low‐ to low‐certainty evidence, we are uncertain about the efficacy and safety of ivermectin used to treat or prevent COVID‐19. The completed studies are small and few are considered high quality. Several studies are underway that may produce clearer answers in review updates. Overall, the reliable evidence available does not support the use of ivermectin for treatment or prevention of COVID‐19 outside of well‐designed randomized trials.”

-

Consider whether I should read the article. Normally I would suggest this is best practice, but given the reputation of Cochrane Reviews and the state of my rumbling tummy, I decide I should probably go review some breakfast instead.

Was this post helpful? Do you use other techniques when searching for information? Let me know in the comments below! You can also subscribe to future posts by clicking the paper aeroplane icon at the bottom of this page.